|

After 20 days, over 50 conversations, about 12000 miles, and a lot of grilled cheese sandwiches I'm on my way back to Brooklyn.

I met cowboys and ranchers and lawyers and police officers and waitresses and teachers and sandwich artists and gun makers and factory workers and students and mechanics and eccentrics and small business owners. They generously gave me hats and maps and books and photographs and fireworks and mugs and pens and nuts and home cooked meals. I made a few new friends, promised a lot of people coffee or a drink in New York sometime, got in some debates but no fights, and got interviewed for a local paper or two. I've got lots more stories and pictures and video to share as I collect my thoughts and reflect more deeply on everything I experienced. I'm not sure what exactly I'll make of it all, but I do know that my view of the country changed - not that my values or beliefs are different - just that I feel a kind of complexity that I can't quite yet describe. It was heartening to spend time with people - grappling with questions together and asking hard questions and disagreeing and challenging assumptions. I'm lucky to travel quite a bit, but rarely for this long and never alone. That experience stirs something new in me that is beyond just missing familiarity of place or the comfort of things. It is homesickness in a way that is new to me: a knowledge that I am displaced - present here and yet belonging somewhere else. It makes me think of the many people who are much more displaced and with so much less power over the experience. Impossible for me to imagine a pain like that. It is hard as the end nears. I trace my path hours into the future - a drive through the gradually flattening landscape as Appalachia slides towards the sea, onto an Amtrak train from Baltimore headed into Penn Station, and finally to a perfect little apartment on a sleepy block in one of the world's great cities, where my favorite person lives and makes it the only place I know how to call 'home'.

0 Comments

Back many years ago I saw the Dalai Lama speak in Chicago. Someone asked a question about anger and his response stuck with me all these years. He said that anger is really just fear. When someone presents anger to you or is angry at you the way to avoid responding in kind is to ask the question, "What are they afraid of? What about this moment or me or this topic do they feel threatened by?" By seeing anger as a symptom of fear we open the door to empathy with another.

In the months since the election I see tremendous anger in friends and colleagues and students and certainly myself sometimes. It isn't hard to look deeper and see how much fear feeds that fire. Fear of violence. Fear of loss of liberty. Fear of further marginalization. Fear for friends and loved ones. Even fear of the anger that seems to be coming towards liberals from conservatives. The anger of people we disagree with or who's lives seem 'other' is far less scrutable. Their anger (especially on television or online) looks like it is entirely about hate of me or my friends and neighbors. It has no context. They have no context besides the frame I already built for them. My visits with people on this trip helps scratch away at the anger that was so visible in the campaign and is still a major part of how the President himself communicates. In meetings with people I hear themes of fear. There is genuine fear of violence. There is real fear about the economic security of their communities. There is an abiding fear about a loss of rights. There is a fear that people who don't know them want to tell them how to live their lives and judge them for their beliefs and identites. There is a fear of the government. These fears are, of course, utterly familiar. I hear them all the time from friends and colleagues. I share some of them. When I tell my hosts that people in the city share many of those fears there is a kind of shock. The source of the fear in urban and rural areas is, of course, often the other. I am trying hard to describe our fears and listen to theirs. We can and should have a conversation about the reasonableness or rationale behind fears. Some of what I hear is based on erroneous information or out and out dis-information. Some of what I see on the left is too, if I'm honest. On many occasions someone quotes a story or event I never heard about. Sometimes I look it up and it did, indeed, happen. Often it was a tiny event that served as evidence for what someone already believed and a media outlet stoked the tiny story for days or weeks. The result is utter amnesia about the event on the left and a mythos around the event on the right. The people I meet aren't stupid or even unsavvy media consumers. They largely see Fox News, for instance, as a biased source. They just see it as biased in their direction. For many people I speak with, the anger at Trump from the left is totally mysterious. It seems childish and poor sportsman-like. They don't ever hear about the fears that motivate it so the way it shows up in their newsfeed is a curated set of memes or stories that decontextualize the circumstances and turn human beings into cartoon characters. It reminds me a bit of the cartoonish and homogenized version of 'Trump supporter' I see in my own feed. I'm not against anger. It is a great motivator and we are biologically built to use it in response to danger. The problem is that our anger is a currency that other people now use to turn into clicks and shares and, in turn, currency for their pockets. The internet is full of alchemists and our health and our democracy is being mined for their profit. This requires our participation and right now we are all readily giving it. I've met lots of people I disagree with about almost everything. The one thing we agree on is that we are being used against one another for the profit of others. The alchemists already have their formula down, so the rest of us better start experimenting together with new formulas if we want to get free from our fears. I think a lot about how this trip is possible without substantial fear or risk because I'm a white man. I tell many of the people I meet that friends and colleagues back home told me to 'be careful' on the trip. Almost everyone laughs at the thought. They think I live in the dangerous place full of strangers. They know everyone around here and see them all as harmless. Often this discovery - that people in both places see one another as dangerous - opens the door to talking about race and religion. We talk about how few people of color and non-Christians live in these counties. We talk about why that is and, sometimes, what it might be like for someone who feels 'other' to move here. We talk about the way different groups are represented on television and on the news. We talk about the difference between people being nice and feeling like you belong. The more liberal folks I meet talk about the struggle of how to confront biased comments by neighbors and family in a way that helps them see their blindspots without reacting with the anger they feel. What improves the chance of making lasting change instead of simply winning an argument? Some give up. Some persist. It is harder to 'unfriend' the person saying those things in a town of 1000 people you see every day or week. Lives are intertwined inexorably.

There are many thoughts to roll around and unpack about this in the weeks and months after this trip. I will say that I find people willing to engage on these issues - even when they know we likely disagree and even when I point out parts that might be invisible from where they sit. I'm not saying I'm going around managing to transform views, but I do think I see that seemingly closed doors are cracked open in surprising ways. It isn't easy to be patient in the face of real disagreement over fundamental issues of equality. The think what I find most is that people are hungry for information. No matter how many hours of news someone reads or watches, a real person from a real place that is unfamiliar carries the weight of experience in their words. I feel that as I ask about these places. I experience that in the curiosity and questions I hear about my life and those of my friends. I'm an imperfect messenger in nearly every moment. At the same time, I believe strongly that each of us has to use the privilege we have to enter spaces other people can't and engage in uncomfortable ways for things to improve. I've yet to meet a stranger who things people who disagree should talk to one another less. The only real question - and the one I'm trying to understand - is 'how'? There is a certain ambiguity that comes with specificity. Half way through my trip the conversations and moments I most reflect on are not the pro-gun rancher or a climate change denying coal worker. These fit neatly into an existing narrative about the deeply grooved divides between urban and rural or liberal versus conservative. Instead my mind lingers on the NRA member that believes in better gun control and that police need much more training to avoid shooting unarmed civilians. I marvel at the people of color who believe everyone has equal opportunity or support Trump's hard line on immigration. I see more and more that there is no checklist of characteristics that inevitably lead to a prescribed set of beliefs. Nearly everyone has upended some expectation. This is, of course, the point of the trip. Still, it will be a while before I know how to organize these into a new point of view.

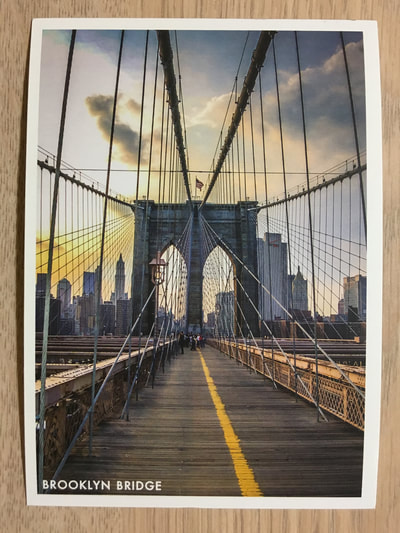

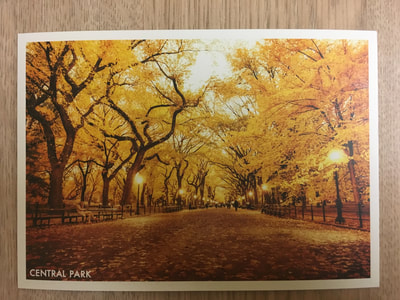

Lately when someone says they're glad I'm getting out and seeing 'real America' I ask if they'd like to pinch me to see if I'm real. They usually laugh, caught by their own absurdity. Still, I don't think my quip exactly dissuades them from the nagging belief that I live somewhere less legitimate. I'm getting closer to understanding what some people mean by that. Many people in these counties do work that is vital to the way all of us live. That work is totally visible and in the foreground here but mostly invisible to people in cities. Some think we take that work for granted and live more easily than them off the labor of their bodies. That steak was raised by a guy who almost certainly disagrees with many things someone sitting in Brooklyn eating it thinks. That electricity powering the laptop that reads a digital subscription of The New Yorker may well have been dug out of the ground by someone who wouldn't be caught dead anywhere near New York. At the same time, the GPS tracking software that allows a farmer to cover more ground with less backbreaking labor was probably designed by someone sitting in an urban office who went to one of those liberal elite colleges. Those urban liberals also help cover the cost of infrastructure and subsidies that anti-government-handout conservatives need badly given how spread out populations are in rural areas. Each side, as it were, is benefiting from the other as it judges the other. Each person is ignoring their own contradictions or hypocrisies. I keep catching a glimpse of a way we could be communicating with one other. I can see, for a moment, someone hearing my point of view or taking on board a complication they don't experience where they live. I listen to a worry or value they think is discounted and often hear complications I never thought about. I imagine and offer a kind of compromise position on the issue. I see them leap to embrace it - surprised by any idea that isn't absolutist. I don't know where that goes beyond those rooms, but it makes for some really hopeful moments between strangers. I'm recording nearly every conversation along the way. I'm taking a picture with each person. I'm writing lots of notes to remember the moments and images the audio recorder fails to get. I'm taking some video here and there to capture these places - all of which are truly beautiful. I have no idea what, if anything, to make of all this when I'm through. For now I'm just making connections. I went to Strand Bookstore a few days before my departure and stood in front of the endless racks of postcards for $1 near the checkout. There's everything from the classic shots of John Lennon wearing that New York t-shirt to the ubiquitous "Gay St." street sign and a sizable number of cobblestones and tall buildings. I had this idea to engage in a kind of reverse tourism - to hand postcards from New York City to people that took the time to visit with me in their home town.

Staring at the variety I struggled to make sense of the message I wanted to send or imagine the audience for the cards I'd yet to meet. A few in particular drew me in and began to fit a pattern. I thought the cards might serve as a tangible version of my larger goal: to create connection and to try to find overlapping values. One of Central Park in autumn and another of the Brooklyn Bridge capture utterly recognizable places, but also great public works - a symbol of the beauty and practicality that is possible when government thinks big about infrastructure for the community. Having the government support and fund these kinds of projects seemed like a potential point of shared values between me and my imagined hosts. I nearly skipped one of the Statue of Liberty. At first it seemed too touristy or hokey. Now it feels like the best pick, though. Here is a symbol that is unapologetically American and embraced by citizens of many political beliefs, yet it was a gift of a European country (France no less!) and is an enduring symbol of our historic (if complicated) welcome to refugees from around the world. At the end of each conversation I give my host a postcard. Sometimes these places and symbols come up in conversation and it's great to have a photo of the very spot to give them. Other times I let them pick which one they like best. On each, I write a little note about our visit and something encouraging them to come to New York. I include my cell phone number and offer to show them around if they visit. Most people I meet won't come or wouldn't be able to make a trip like that because of health or finances. Still, I hope just knowing they have a willing host across the country in a place that seems so 'other' softens their thoughts of those of us that call it home. A country band from New Mexico mounts the flatbed truck turned stage adorned with red, white, and blue bunting and a cloth banner with the word 'welcome' stitched into it that hangs down barely grazing the dirt lot next to the public park. At this point the line for food (a set of aluminum pans filled with beans, fish, hot dogs, and fries) stretches past the bouncy houses and to the covered picnic bench set atop a concrete slab. Behind the park's toilet facilities several large metal pots full of oil and heated by well tended wood fires in their lower chambers give off immense heat as a group of men from the volunteer fire department keep the food coming and rib one another about this or that the way some men do when they feel affection.

Several of the men chat with us and one spends a while telling us about his family's multi-generational history in the town. We talk about differences and about resistance to change. He tells a story about his grandfather housing and employing a Japanese family for about fifteen years around World War II, even as others lived in internment camps in this area. His grandfather considered them family and stayed in touch long after they ultimately returned to California. He offers this as a story about how, when you know people personally who are supposedly 'enemies', it becomes clear that nothing is quite so simple. It is totally relevant and exactly the kind of argument I would make against the 'Muslim ban' or 'The Wall'. I admire the progressive values of the story and his grandfather's humanity. Still, as he tells the story he uses the word 'Jap' to describe the family repeatedly. He says it plainly and without malice. It's a word I don't think I've ever actually heard someone say in conversation. My guess is it is the same word his grandfather used to describe these dear friends he cared so much about. That is the kind of paradox I experience over and over again here. Points of connection and shared values rise up and I thrill at the discovery. Then a word or idea or bias or assumption gets dropped in and adulterates the mixture. Do I focus on the points of connection? Do I challenge the use of language? How do I help him see what we share without shutting him down through 'correction' or pretending that there aren't real disagreements. I told myself my mission was to spend time learning more about the places most different from New York and how their lives and values and histories contribute and lead to some of the thinking and politics that feel so foreign to me. At the same time, I know part of that is finding a way into conversations that don't shut people down by proving what they might suppose - that I'm some judgmental costal elite that is here to police their thoughts and look down on their way of life. He, like many, is puzzled by the very idea of living somewhere like New York City. Many can't fathom having a desire to even visit a place they perceive as so crowded and dangerous. My stories of giant parks to get lost in and neighborhoods and kindness and other ways to form community than geographic proximity are revelatory and inscrutable in turn. For days now the men I meet tell me I have to try "cat fries" at the 4th of July event. I don't know what these are. I'm sure they aren't cats, but I'm also sure they aren't vegetarian. One guy runs up now with a paper basket full of irregular breaded nuggets of some kind and offers me one. He eats one and holds another out to me. I politely decline, but that isn't going to be sufficient. I out myself as a vegetarian... which doesn't seem to strike him as relevant to this particular situation. He's sure I can try one. Eventually he gives up when I learn that "cat fries" is a euphemistic name for fried and breaded bull testicles. Back home in New York this interaction would feel cruel or disrespectful. This man isn't either. I find out later he's married and a step-dad to two kids. After his first date with his now wife he had to take a trip out of the country. On his first day back in town he showed up at 6:45am to her house with t-shirts for her and her kids. He was too excited to see her to wait until a reasonable hour. She raves about what a kind man he is and how different he is than so many others that treated a single mom like a, "piece of meat." He couldn't care less if I eat bull testicles or not. It was about trying to share something local with a stranger to make him feel more like a part of the community. We circle the park once to get a sense of the event. Doing this in a town where you are told everyone knows everyone else feels a bit like a coming out party. There are three kinds of responses: disinterest, interest, and intense interest. We've been here nearly a week and at this point people know my name everywhere I go without introduction. It is a feeling of minor celebrity, though hard to own or feel much about because it was earned merely through existence. I want badly to spend $5 to throw six balls at the dunk tank. The price, though a bit steep, isn't what stops me. Nor is it empathy towards the target. The man is already drenched and seems good natured about the whole thing. We overhear that he is the local principal, which makes sense. It certainly explains the long line of young kids throwing with a kind of glee reserved for guiltless revenge. Mostly I'm stopped by a fear of failure. It is one thing for some ten year old to miss and then be given the consolation of having gotten 'close enough' so they allow him to push the target by hand and plunge a local authority into the giant plastic tub. It is entirely another thing for the New Yorker to step up with his Keen sandals, Goorin Brothers hat, and two theatre degrees and fail to hit the mark. I see my fear play out when a local family plops down to watch. A serious looking dad and two teen children set their folding chairs down front and center. There is a small dance of what chair goes where and who sits in which. The reasons for these adjustment are mysterious - all the chairs are identical. The teen girl is tall and strapping. She carries a kind of robust confidence without much effort or pride. The teen boy has that tell-tale curve in his upper spine and slightly shaggy hair that telegraphs he spends many walks down school hallways with eyes aimed at the floor trying to be invisible. I immediately feel a kind of sympathy for him. The park is full of big men with big hats or voices or both. Many of these are men who work outside and spend their days yelling over the sound of machines or across distances. They drive big machines. They train or handle or kill big animals. Their bodies are their office and their paycheck. The boy is not one of these men. He gets up to take a turn dunking the principal and I feel worried for him. His first pitch is wide. No worries, these are not exactly regulation baseballs or anything. Anyone would have to learn their weight and how they fly. The second one is high. Very high actually. It might have been better if each throw after that was a kind of learning process getting him closer to the target. Instead he settles into a rhythm of equally wide throws - a maddeningly inept consistency. After the last one he turns to walk away and the mom of a small child gives him a retroactive tip that is as useless as it is embarrassing. As he arrives back to his family he lifts his eyes and says to his dad, "I told ya I can't throw. I never could!" He says it with a laugh, but there is enough edge in his voice that he doesn't get the kind of ribbing the men here usually give one another about minor failures or mistakes. The teasing would feel too true. Just about the time that blip of embarrassment was fading his sister got up to take a turn. Immediately this seems bad. Even the way she paid her $5 has a kind of flourish and expertise. The first throw misses, but hits closer than her brother ever did and smacks the canvas backing with a whack that reverberates and makes her potential victim take notice. It is either the second or third ball that lands hard at the center of the target and dunks the principal to the laughter of the crowd. It gets worse. She's only used half her throws and manages to dunk him a second time before it is through. Her victory lap back to the family includes at least one high five. Her brother doesn't look up. We end the night with fireworks. In Oklahoma fireworks are legal and ubiquitous. My teen years included some amateur fireworks displays in New Jersey of questionable legality. I always reassured myself that it couldn't really be so bad if UPS delivered them and allowed underage kids to sign for the package. That was, of course, before 9/11 and I suspect mail order explosives are harder to come by now. Not so here. Rather than having a town sponsored professional display there is an unpaved lot between the park and the high school football field that is designated for a kind of crowd sourced fireworks demonstration. We light off many, basking in the guilt free feeling that comes from doing something that is entirely legal where you are but illegal where you're from. I remember my dad and I meticulously planning shows in our backyard, focused on the best order for the fireworks for maximum effect. He understood theatrical structure without realizing it. I have one of those moments you have when you lose a parent - that ache to call and tell them something so very small. The sunset is an event here. There's rarely something to block the view and very little to destroy the awesome vastness of the night sky as it appears. We watch the cars depart, nearly all pick-up trucks with their lights sweeping the thinning crowd as they turn to go. I have not been here long but I do see a piece of what they love. I can just now begin to imagine how a television full of hundreds of stations of people who don't sound like them in places that don't look like home and with lives and ideas nobody around them shares seems like a kind of lifestyle siege. Many told me that independence means freedom to live the way you want without others imposing their values on you. I think a lot of liberals like me basically agree. Sometimes though, no matter how big the country is, we will find ourselves standing face to face both wanting our liberty right then and there. In those moments, who gets to be free?  I arrived Thursday eve, traveling LGA>DFW>AMA and a two hour drive north across the Oklahoma border and up to Boise City. I heard that a local gas station/convenience store was a good spot to spend the mornings as a variety of people stop in for a bit to have coffee and chat. Jamie (who is on the first leg of the trip with me) and I went there about 8am Friday and within seconds of asking the clerk at the counter rattled off every person or family who would be in and what time they show up. She was right, and within minutes people began to arrive like clockwork before heading off to their jobs. The community is a mix of farmers, ranchers, business owners, and people working in service jobs that one might find in any community. Within the first 12 hours a few different folks we hadn't met walked up, knew my name, and introduced themselves. As one person joked, "You're pretty sure if you don't recognize someone they're not from here. If three locals get together and don't recognize someone you know they're not from here." I'll certainly have lots to share when I come home from my travels but it seems worth saying right away that, as one might imagine, no place is all one thing. In the two days so far I've met with, shared a meal with, or spent time with five people. Their histories and lives and political perspectives and experience of their community and the world is as varied as you can imagine. I'm not a fan of think pieces written before the author has had real time to think, so I have nothing profound to offer at the moment. That said, I'm already incredibly glad I'm doing this. It is scary to call or walk up to total strangers far from home and who you worry you have very little in common with. It is moving to discover connections and share our stories. It is impossible to walk away from an hour or many hours sharing space with a person and listening to one another and not feel like you are closer. Sometimes even friends. I'm happy to piercing my bubble and grateful for the chance to share a bit about my life in New York that pierces some in return. Photo taken sitting on post marking where Colorado, Oklahoma, and New Mexico meet. |

AuthorScott Illingworth is an Assistant Arts Professor in the Graduate Acting Program at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts and a freelance theatre director. Archives

July 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed